self

The Identity of Self

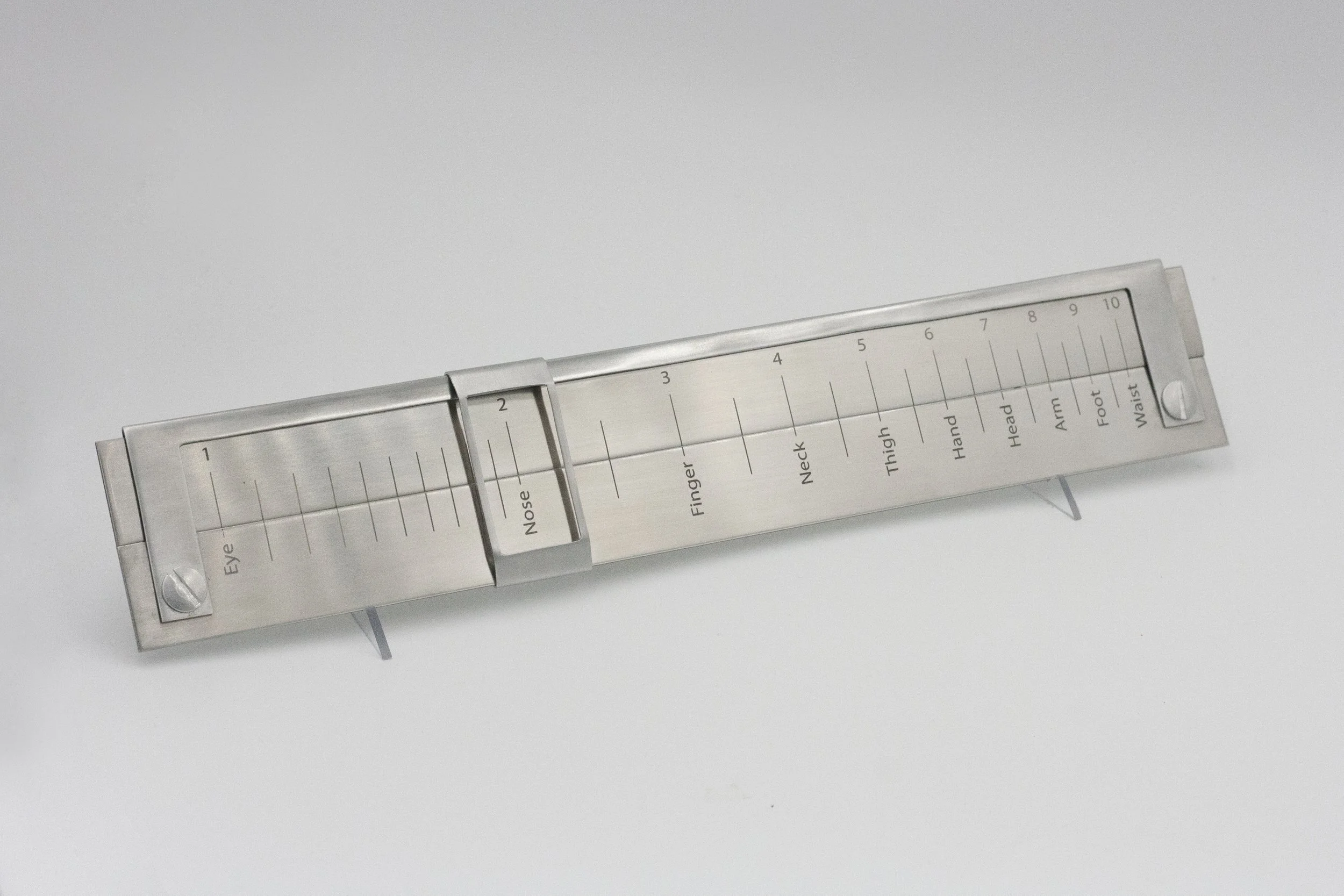

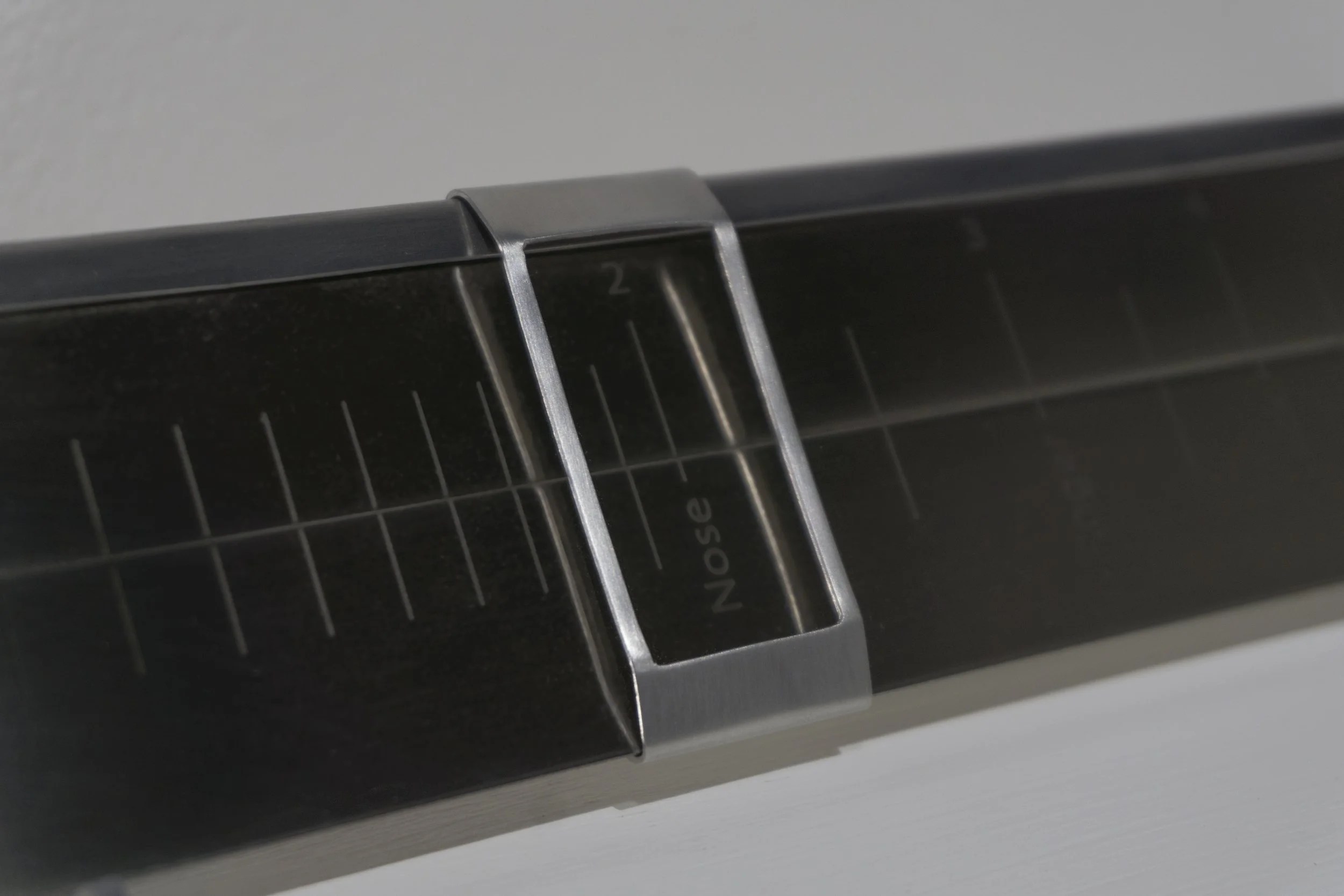

After two years of making Self, I spent time reflecting on the series as a whole and its conceptual orientation. Originally, I always limited my statements to include only a dialogue of objectivity and mathematics, disregarding any greater context. It is after this time of reflection that I acknowledge that the extreme and nearly obsessive attempt at objectivity is rooted in issues of identity. In a further expansion, I would add that these issues are a result of a larger cultural context.

All of these concerns are addressed in an essay on the use of the body in a 1990’s video art piece by Ewa Lajer-Burcharth. This essay discusses work very different from my own, but there is an excerpt which poses highly relevant questions of identity and the self:

“How does one come to inhabit one’s own body? How exactly does one’s own anatomy participate in producing and maintaining one’s imaginary and symbolic coherence as a sexed being? And how may one negotiate one’s relation to one’s own flesh with the visual culture and image-based technologies that are crucially involved in the production of one’s sense of self?”

I find this excerpt as an eloquent lingual summary of the thoughts that arose during reflection of my work. Through this reflection, I realized that my works are dealing with the negotiations between sense of self, symbolic self, physical self, and even the sexed self.

In the use of mathematics, my artistic process shows a unique relation between my mental presence and my body, one that is an attempt to entirely separate and objectify the two from each other. This separation allows me to focus on each entity to try to grasp where Hattie lies. In one way, this disengaged clinical treatment of my body renders it a mere inhabited object, no more important than any other physical item. My body is isolated and un-personal, non-ideological and empty. In my inherent femaleness “as a sexed being,” this realization can be a comforting and powerful reaction to body politics. Physical anatomies contain no theoretical and personal power or value. Authority lies within the theoretical self, the one that communicates and thinks.

This is not my only answer to Lajer-Burcharth’s questions, however, as it is also in this disengagement that I find no true Hattie within myself. With this perspective, the reduction of my body into mathematics serves as the only finite representation of Hattie, and any other is inaccurate, or even more truthfully, insufficient. Qualities of the personality, and individualistic habits, traits, interests etc. are immeasurable and fluid, never amounting to finite calculations, and as a result they have no defining power.

I am already aware that my need to mathematically calculate my body is a result of the “visual culture” affecting my mental self. It has convinced me through “image-based technologies” that my projected self is insufficient; there has to be a real Hattie. And yet, in my search of this Hattie, am I giving the culture what it wants? Or are these thoughts of non-identity insufficient for the culture in which I exist? I am told that both my power lies in my physical and also in my mental self. If my body isn’t standard, I am not of value. If my intellectual self isn’t original, I am not of value. In my work, I have searched both options, desperately attempting to grasp upon one final conclusion and, though fruitful, it is all caused by the manipulation of my culture.

In my inability to rest on any one answer, new questions arise. Is there a Hattie? Can Hattie be found in a body, an intellect, or neither? Perhaps the symbolic identity I am seeking does not exist, and yet, having been assured by my own culture of its existence, I have spent two years searching for it.